|

||||||||||||||||

| virtual Studio | References | Workshops | Style of Frames | History | Collection | Gallery | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Press Release |

| |

|

|

||

Der Kunsthandel, Issue 11/2004, Pages 42 - 45 Frame manufacturer Karl Pfefferle in Munich Exact replicas of historical frames The frame manufacturer Karl Pfefferle has been handcrafting quality frames to suit the very highest demands for generations. Even the trained eye can hardly tell the difference between the Pfefferle replicas of historical frames, covering 5 centuries from Gothic to Art Nouveau, and their originals. The tradition of the company itself, which comprises five generations, stands alone as an independent chapter in Bavarian arts and crafts, and in this connection includes the preservation of historical artworks over the last 145 years: in 1859 the great-grandfather of the present proprietor established the Pfefferle Framing and Gilding Workshop at Number 30 Brienner Street, the oldest specialised business in Munich. His son Karl Pfefferle (2nd generation) relocated the workshop to its own quarters at number 6 Türken Street, and started setting up the collection of frames that formed the foundation of the present wide variety of individual, handcrafted and customised frames. During this time extensive re-framing of pictures for the Old and New Pinakothek ensued. The workshops expanded to cover restoration contracts from churches at home and abroad. The present-day proprietor is Karl Pfefferle, who took over the running of the company in 1967. The headquarters of the parent company in Munich’s museum district had to make room for the construction of the Old City ring road, so the company then moved to number 5 Gewürzmühl Street not far from the House of Art. Up to the present day, the Pfefferle business has framed approximately 70 masterpieces of European art history, from Albrecht Dürer, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Peter Paul Rubens, and Jacopo Tintoretto to Francois Boucher, and all in keeping with the historical originals. The Pfefferle frame collection is the most significant collection of historical frames in the South German region. The collection grew over a period of more that one hundred years and contains over 2000 original historical frames from almost all European countries. It documents the history of the frame from its beginnings as a simple Gothic window frame, through all the epochs: Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Classicism, and Art Nouveau up to Modern. In 1999/2000 in the Salzburg Baroque Museum an exhibition was dedicated to picture frames of the 16th and 17th centuries with frames from the Karl Pfefferle collection. The main focus of the exhibition was on frames from the South German Baroque and French frames. For comparison, examples from Italy, Spain and The Netherlands were chosen, and a classification of the frames according to art historical and technical aspects was worked out; further proof of the competence of the company. The Pfefferle company does not just embrace private persons as customers but also, on a regular basis, museums: for the re-framing of “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” by Franz von Stuck for the Villa Stuck in Munich (illustration bottom left), for example, it was possible to draw on the firm’s own resources, because there were already several of the painter’s original frames in the company’s collection. At the same time, it was necessary to investigate thoroughly in order to find as near a match to the original frame from 1918 as possible, because there was no longer any documentation available. The focal point of the collection are frames from the 20th century, among others Emil Nolde and August Macke, as well as models produced according to designs by Bruno Paul and Bernhard Pankok, the architects of the United Workshops in Munich. Comprehensive archives The core business of the company today is the production of individual replicas of historical frames in accordance with master copies from the in-house collection. In this field the company enjoys worldwide renown. The in-house gilding workshop has at its disposal a comprehensive archive of casting mouldings and illustrations of historical ornamentation, and over 6000 technical drawings of cross sections of frames. The frames are individually handcrafted according to traditional handicraft methods, and, after up to 30 hours of labour, about 800 to 1000 frames leave the workshop per year. Special value is placed on the individual response to all requirements in connection with colouring, breadth of profile and the ageing patina. In particular, to achieve a convincing imitation of the signs of wear and tear, and to obtain a natural colouring in the ageing process is one of the most difficult challenges on which the vivacity of the replica hangs. Frames as well as special projects are produced in the in-house carpentry workshop; the gilding workshop also takes on the painting and gilding of sacral objects, furniture and sculptures. Eight gilders (the old guild name is “Fassmaler” i.e. painter and gilder) work here, some of them in the 2nd generation already. Since the 1960s well over 50 apprentices have been trained in the gilding workshop. In collaboration with restorers from the areas of painting, paper, wood, furniture and sculpture, advice is given and service provided on site; this belongs just as much to the company’s accomplishment spectrum as choosing a frame from a master-copy that is sent back either by post or by e-mail. The leading authority here is Michael Pfefferle, who mounts |

several suitable virtual frames to scale around the picture to be framed, and transmits the frame suggestions to the customer. This is a method that saves the customer the bother of travelling and having to transport precious paintings, and also reduces the inhibition of potential customers to make enquiries. Parallel to the historical framings, works from contemporary artists (such as Sigmar Polke, Georg Baselitz, R. Penk et al) are also framed, and new frame concepts are developed together with the artists themselves. The company-owned gallery Even the artists themselves sometimes succumb to the fascination of beautiful frames and apply their own handiwork to the crafting of the frame. Due to contacts with contemporary artists, a company-owned gallery came into being in 1983. At first it represented artists of the New Figurative Painting, but since the 1990s the Gallery has increasingly directed itself towards a more conceptually aligned painting style. The Karl Pfefferle Gallery, which represents contemporary artists such as Alighiero e Boetti, Jiri Georg Dokoupil, Rainer Fetting, Sigmar Polke, and Bernd Zimmer et al, belongs to a community of interests called “Galleries at Gärtner Place”. This alliance in cooperation sends out invitations to private viewings, and every summer it also organises a special themed exhibition. Dr. Christiane Wolf Di Cecca Frame manufacturer Karl Pfefferle in Munich Der Kunsthandel, Issue 11/2004, Pages 42-45 |

|

|

|

||

Architectural Digest 11/2004, Issue Nr. 54 18:10 at the viewing These newcomers are absolutely worth seeing (from the top): red-based chessboard-viscose “Rumba Velvet”, around 205 Euro per metre; framed in black is the check-taffeta “Rio Taffeta Check”, around 190 Euro per metre; both from Mulberry. Left is Ashley Hicks’ “La Fiorentina” in red, a design that his father David in 1966 created for the wall-to-wall carpeting of a house in London, around 165 Dollars per metre. All three historic frames are on loan from Pfefferle, Munich. On the wall is shimmering the linen-velour “Tiziano” by Colony, around 200 Euro per metre. The bench has been covered in Ashley Hicks’ “Little Clinch”, around 130 Dollars per metre. Lying thereon is Peggy Guggenheim’s “A Collector’s Album” by Rizolli. The standard lamp “Tuba” is by Anta, around 710 Euro. Architectural Digest 11/20004, Issue Nr. 54 |

|

|

|

|

||

Handelsblatt, 23rd/24th/25th April 2004, Page B 2 Snipping around is forbidden Only a good frame merchant can accord the artwork a suitable presentation “The frame gives a picture dimension”, explains Ulrike Ertl, M.A., of the Albertina Museum in Vienna. Without a framework the two-dimensional artwork would “flow into the wall”. In this way a frame is equal to a window that allows a glimpse of something visible. Just how applicable this is, is demonstrated by the early frames of the 15th century: as the panel painting became established next to the altar painting and was separated from a solid anchor, the bottom profile rail of the frame often had a bevel cut, just like windows. However, although frames formed the most important interface between wall, artwork and space and at the same time protected it, they were for a long time neglected. Karl Pfefferle, who heads the framing workshop established by his great-grandfather in Munich in 1859, estimates that approximately 98 per cent of all paintings no longer rest within their original frames. A change of ownership was the most frequent reason for this. For example, August the Strong had his collection, including paintings by Dürer, mounted in Rococo frames. Aesthetic compassion was not available then. Pfefferle: “A new frame expresses the statement, “This is mine”. A picture is more easily painted than framed. However, it was not only the nobleman collecting pictures that placed no value on original frames. Even museums liked to give their stock a unified look. “Frames were simply a container for the drawings”, as the restorer Ertl says about the frames in the Albertina Museum. It was a case of neutral frame borders without any stylised features. This opinion has changed dramatically. Since Klaus Albrecht Schröder took over the running of the Albertina Museum, exhibitions are laid on that appeal to the public – the trend tending towards the style of the relevant epoch. Put more clearly, this means: take away the museum’s frames and replace them with the historically correct profiles. Not only is the Albertina Museum currently exchanging about 180 frames a year, but also the Liechtenstein Museum that opened in Vienna in the spring of 2004 presents itself in its entirety as a piece of Baroque artwork, and is therefore having its pictures framed in the correct style. The person searching for a true-to-style frame that goes beyond profiled rails simply glued together has two possibilities: either he goes to a dealer specialising in old frames, or he has a replica frame custom-built. Both options are simply a question of money, although in view of the hourly wage today and the fact that up to 15 stages of labour are required, a reconstructed frame is not necessarily cheaper than the original. From one to ten per cent of the value of the painting should be calculated for a custom-made frame. When long-established picture framing companies like Pfefferle in Munich or F.G. Conzen in Düsseldorf (established 1854) can profit from the willingness of museums to re-invest in their picture frames, it is in the main due to the fact that both businesses own large collections of over 2000 old frames each on which they can draw. They can replicate historically accurately almost every profile from the 15th century to the modern day. Therefore, Karl Pfefferle had the advantage a few years ago when Franz von Stuck’s “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” was to be re-framed, because he had several of the painter’s original frames in his collection. At the same time, it was necessary to do a thorough search in order to find as near a match to the original frame from 1918 as possible, as there was no longer any documentation available. The artist, for whom, as was well known, the frames were an integral part of his artwork, had invented a kind of flexible standard framework – the multiple-plane frame. Only a frame of this type came into question. Add to this Pfefferle’s work ethos: “Work with humility. The picture is centre-stage, not the frame.” |

Picture of the frame: Pfefferle  Pfefferle’s son Michael, who can make several different virtual frame suggestions for each picture and then send them on by e-mail, has proved the fact that old-fashioned handicrafts and modern communication methods complement each other. This is a method that first of all saves the customer the bother of travelling and having to transport precious paintings, and also reduces the inhibition of potential customers to make enquiries. (see virtual studio) When asked how to find the right frame, Georg Friedrich Conzen says first of all how it is not to be done. “If someone comes along with a photo of his sofa we say: The first thing is that the frame has to suit the painting.” The rest is, in the eye of the Rhineland frame manufacturer, above all a question of the proportions. The feeling for the right size, however, seems to go more and more astray in times like these. Good advice is therefore paramount. The painter Alexander Jawlensky once claimed that it was easier to paint a picture than to frame it. Christel Reuther, who has been dealing in frames in Munich for over 20 years, also knows this. “People used to buy old frames because they were much cheaper.” Those times are long gone. Reuther considers advice about style to be the be-all and end-all in the search for a frame. Breaking with style is trendy “An Art Nouveau frame does not suit a Baroque painting.” On the other hand, by consciously breaking with style, optical tension areas can be constructed – a strong trend momentarily. Even Picasso preferred heavy, historical frames for his paintings. Of course, in the case of taking such optical risks, the trained eye was indispensable. It all depends on the aesthetic experience of art dealers and frame manufacturers. “Because every frame alters a picture in a colossal way”, adds Reuther. Presumably, Olaf Lemke in Berlin has the best eye in the business of frames. He has been dealing in frames from the 15th and 16th centuries since 1969, and, within his magnificent rooms, practises the art of hands-on stylistics. Among his customers, collectors such as Heinz Berggruen, and just as equally artists such as Georg Baselitz, are to be counted. He has also been taking care of the Pietzsch collection for many years. With his historical frames, Lemke is manoeuvring on a level of high quality where the picture framework itself becomes the object. Is the frame too small or too big, then the picture just had some bad luck. Lemke: “I do not have products that can be snipped around at – or would you cut 10 centimetres off your picture so that it fits the frame?” Tinga Hornay Snipping around is forbidden Handelsblatt, 23rd/24th/25th April 2004, Page B 2 |

|

|

|

||

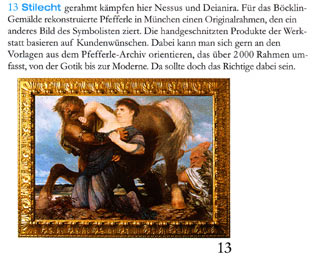

Architectural Digest 3/2004, Issue Nr. 47 Nessus and Deianira are fighting here true to style. In Munich, Pfefferle reconstructed an original frame, which adorns another picture by the Symbolist, for this Böcklin painting. The hand-carved products of the workshop are based on customers’ wishes. To this end, one is invited to use, for purposes of orientation, the master copies in the Pfefferle archives, which contain over 2000 frames from Gothic to Modern. The right frame is certain to be among them. Architectural Digest 3/2004, Issue Nr. 47 |

|

|

Süddeutsche Zeitung, 23rd November 2001, Page 43 In accordance with secret recipes Because pictures need a frame For a long time picture frames were dependent upon the tastes of the time, and were matched to the fixtures and fittings in keeping with fashion. When a picture was bought, the change of frame was supposed to make a statement about the new owner. August the Strong had his coat of arms inserted into the exuberant Baroque carvings, which he used to frame his Dürer and Cranach paintings in the manner of Ludwig XIV. “Choosing an authentic frame that matches the style of the time when the picture came into being, is a relatively new phenomenon,” says Karl Pfefferle, who runs a business workshop creating replicas of historical frames. At the time his great-grandfather began collecting frames, no one was interested in these old pieces. That did not start until the 1920s. “In this respect, he was far beyond his time.” The great-grandfather, who was trained as a facade painter, came to Munich from Tyrol and in 1858 he founded a business as a church restorer and gilder. Picture framing just more or less happened on the sidelines. In 1967 Karl Pfefferle took over the running of the family business, which had grown over several generations and which now had twelve employees. All the stages in the labour process of frame production from wood shaping and carving to gilding are pure handcrafts, as they were in the previous generations. Pfefferle’s grandfather made a conscious decision against industrial, mass-produced products exactly at a time when the business was flourishing. He brought the best pieces of the now over 2000-strong frame collection from France and replicated them by hand using the highest quality handicraft methods. Even today the original models are used as master-copies – masterful pieces from all epochs of art history; plain Gothic with the typical window-sill-like bevel cut on the lower edge, Renaissance models with aedicule and Baroque showpieces. Some of the frames in the collection are slightly damaged. “That doesn’t matter, they are allowed to show their age”, says Pfefferle, who avoids making an all-too-smooth restoration. From the family treasure trove Very often the small signs of damage and broken parts help to impart knowledge about the production process, because it is not always possible to see from the immaculate surface and decoration how they were made. On a small, splintered area of a red, variegated tortoise-shell frame from the 17th century, it is possible to see not only the thickness of the material but also the red undercoat that gives the transparent-yellow natural substance more than ever its warm colouring. Of this model, too, Pfefferle has already made a replica; though not from the shell of a tortoise as tortoise-shell may only be used if it was bought prior to 1960. The faceted and varnished layers of the copy deceptively imitate the original material. “Sometimes you just have to experiment, but exactly that is the attraction”, says Michael Pfefferle. The recipe for the artificially created crackles – tiny, hair-like tears – on a coloured surface that imitates porcelain is a family secret. To imitate convincingly the traces of time is the most difficult demand on which the vitality of the replica rests. In order to achieve the natural ageing process, the gold leaf application has to be well polished so that the underlying yellow and red bole layers can shine through. When, 35 years ago, the Baroque High Alter by Martin Schaffner – a highlight in the Old Pinakothek – was renovated, Pfefferle was most concerned about replicating the Gothic colour combination. However, not always is the authenticity in the foreground. He attempted daring anachronisms on some of the pictures for the Lenbachhaus Museum: the powerful, dark framings of the “Blue Horse” (1911) and “The Tiger” (1912) by Franz Marc were modelled on an Italian frame from the 17th century. A similar thing happened to Rembrandt’s “Cupid with Soap Bubble” from the Liechtenstein collection; the Dutch god of love has for some years now been elevated to nobility by an elegant frame moulding based on an Italian model: |

“This frame is actually not typically Italian at all. Rather, the shape is more like plain Calvin. That is why it suits the Rembrandt so well”, says Pfefferle. The last to leave the workshop was a group of Brueghel drawings for the copperplate cabinet at the Albertina Museum, framed in dark borders and fashioned after a contemporary model. With sand from the Provence There are frames in the collection that have never been copied, and others that are constantly in demand. Approximately 800 to 1000 frames per year leave the workshop, needing about 30 labour hours each in the workshop. In the main, the original at an art dealer’s would be more expensive than the replica, but that is not necessarily the case. A particularly labour-intensive replica can cost up to 30,000 DM. Extensive carvings or so-called etchings, in which the painted layers over the gilding work are again scraped away, demand in particular a great many labour hours. Surprisingly, the gold leaf forms only a very small part of the final cost: roughly 150-200 DM for a medium-sized frame. Nevertheless, it is exactly these 10,000th of a millimetre thin sheets of gold leaf that can create a great deal of work: the adhesion to the underground is dependent on weather, climate and the humidity of the surrounding air during the gold leaf application. Just how well the gold leaf adheres comes to light during the burnishing of the gold leaf with an agate stone. When the sheets of gold leaf start to flake off, the whole day’s production is usually affected and the gold, together with the bole layer, has to be washed off. Careful handling of the material and the old models is practised throughout the workshop; great pains are taken to store the gravure tracings, to arrange the numerous stucco models, and to avoid every draught when the gold leaf is being applied. Pfefferle likes to bring sand from Brittany in order to sieve out the different grain sizes to use for sanding the surfaces of the French Baroque frames. The acquaintance with and love of the material is a family tradition here as well. Astrid Mayerle |

|

|

|

||

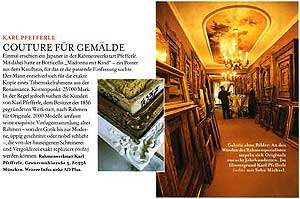

Architectural Digest 5/2000, Issue Nr. 21 Karl Pfefferle Couture for paintings Once a Japanese man appeared in the Pfefferle frame workshop. He brought with him Botticelli’s “Madonna and Child” – a poster from a department store for which he required a suitable frame. The man decided on an exact replica of a tabernacle frame from the Renaissance. The cost: 25,000 DM. As a rule, however, the customers of Karl Pfefferle, the owner of the workshop established in 1856, are searching for frames for an original masterpiece. His exquisite collection of old frames embraces some 2000 models – from Gothic to Modern, elaborately carved or elegantly plain – which can be exactly replicated in the in-house carpentry and gilding workshops. Architectural Digest 5/2000, Issue Nr. 21 |

|

|

|

|

||

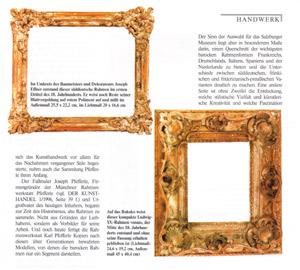

Der Kunsthandel, Issue 1/2000, Pages 36 - 38 Picture frames from the Pfefferle collection in Salzburg Baroque as a touch of luxury Eccentric ornamentations and a touch of luxury – those are the trademarks of Baroque picture frames. They are again highly valued as authentic frameworks for contemporary paintings by collectors and museums alike. The Salzburg Baroque Museum is displaying selected pieces from the Pfefferle Munich collection until the end of January. There the frames are introduced as one aspect of decorative art in the 17th and 18th centuries Baroque was not known to be a time of simplicity and modesty. Splendid, sumptuous and sometimes eccentric were now and again the order of the day in the architecture, arts and crafts, and painting of the 17th and 18th centuries. Even the frames of this epoch lived and breathed the air of the times, as the almost 50 examples displayed in the Salzburg Museum show. Vivacious ornamentations, extravagantly swelling shapes and bold lines do not determine the look of just the furniture and stucco structures of this period, but also the style of picture frame. One of the most impressive and most beautiful exhibition pieces in the Baroque Museum is a French frame from the time of Ludwig XIV (1643-1715), the Sun King who erected the Palace of Versailles. This animated, elegant frame with its high outer profile, finely carved cartouche, pierced Rocaille handiwork, and finely notched surface pattern in the chamfer is without doubt a handcrafted showpiece of Court culture. That this high standard was maintained in France a generation after the Sun King is obvious from a Ludwig XV (1715-1774) period frame from the mid 18th century. Being more compact in design but with the same sculptural quality as the Louis XIV frame, the frame’s elevated edges on the side profiles present themselves with more movement and curvature, so that already the next phase in style, Rococo, is being announced. In its display, however, the Salzburg Museum concentrates exclusively on Baroque frame styles, that is, on types of frames that represent a typical version of a particular time and region. Also belonging to these are the Louis XIV frames covered in continuous Baroque strap work from the period around 1700, which were rediscovered 160 years later by the painters of the Impressionist School. Having been relieved of the remaining gold leaf and preferably coated in a white glaze, they turned into desirable frameworks in the 19th century. During this period, as arts and crafts became especially enthusiastic about replicating past styles, the Pfefferle frame collection also came into being. The Fassmaler (= painter and gilder) Josef Pfefferle, founder of the Munich firm Pfefferle Workshop for Frames (compare DER KUNSTHANDEL 1/1996, Page 39 and following pages), and great-grandfather of the current owner, began at the time of Historicism to collect old frames, not as a hobby, but as models for his work. And even today, the Pfefferle workshop manufactures replicas from these models, which have proved themselves over generations, and of which the Baroque frames are only a segment. The reason behind the choice of frames for the Salzburg Museum was, in high measure, due to the wish to present a cross section of the most important Baroque frame types from France, Germany, Italy, Spain and The Netherlands, and to make clear the differences between South German, Franconian, and Frederician-Prussian variations. Another aspect is, without doubt, the revelation that historical frames fundamentally incorporate within themselves manifold styles, artistic creativity and a certain fascination. One significant type of frame typical of the South German region is unarguably the Effner frame, named after the architect and decorator Joseph Effner (1687-1745). Following his designs, frames were manufactured in the Munich Court workshops between 1720 and circa 1740 for the Prince Elector Gallery in Schleißheim and the Residence in Munich. The exhibition displayed two pieces made by the Effner circle, with protruding corner embellishments and the – as Christian Burchard writes in the catalogue – characteristic freestanding plant stems, called “Springer”. On the other hand, proving that Baroque frames need not always be decorated with lots of projecting ornamentations is the so-called Canaletto frame, a type that appeared at the end of the 17th century in Venice and which originally was used preferably for the vedute (= landscape) works of art by the painter Giovanni Antonio Canale (1697-1798, called Canaletto). This frame, for which a typical feature is the use of “mirrors” – smooth, brightly-polished, gilded areas on the frame rails – seems, in contrast to the majestic French frames, like a Baroque understatement: the ornaments are not very plastic, or three-dimensional, but rather worked in relief or as an embossed surface, whatever the case may be. Because of its discreet elegance, it was also copied in various forms for framings for Princes’ galleries in other European countries until well into the 18th century. Few frames undergo this international imitation effect, mostly limited to one type and one particular region. |

So it was with the Bolognese foliate frame, a frame somewhat heavier, and fashioned with a declining profile. Admittedly it also travelled over the Alps to northern Europe, but, however, replicas of this style are unknown. As a rule, one associates with the expression “Baroque frame”, an elaborately carved, gilded frame. This was, though, not the practice everywhere, as the unadorned Dutch frames made from tortoise-shell and ebony prove. Compared to the predominantly courtly splendour of French Regency and Louis XV frames, and the impressive Spanish frames, they demonstrate the bourgeois, puritan variant of the Dutch Baroque frame. Certainly, the whole spectrum of the Baroque frame has not been expanded in this exhibition. Those who deal with historical frames will miss here at least the sculptural pomp-and-trophy-frames of innumerable Baroque portraits of emperors, which possibly has to do with the practical orientation of the Pfefferle collection. Of course, what indeed would have been good for the exhibition would have been a little more lustre on the surfaces of the frames. The museum itself considers the frames that have lost parts of the paintwork and/or the gold leaf – some parts even right down to the wooden base – as a kind of artistic insight into the frame-making process. However, without wanting to play down the historical aspect, part and parcel of a Baroque frame is the play with colour, golden hues and reflections of light, all of which ultimately give an inkling of Baroque splendour. Crucial is, too, that the Salzburg Museum is trying to direct the focus onto a branch of the decorative arts that has already been researched in detail in England and France, but is still being treated as the Cinderella of art history in Germany. Sabine Spindler Picture frames from the Pfefferle collection in Salzburg Der Kunsthandel, Issue 1/2000, Pages 36-38 |

|

|

|

||

Die Welt, 7th March 1998 Rescued from fading away The Karl Pfefferle Framing Workshop in Munich provides authentic flair A Rembrandt from the Prince of Liechtenstein’s collection was to be re-framed. So Karl Pfefferle (Munich) travelled to Liechtenstein with an assortment of original frames and discussed with the Prince, which one would be most suitable “so that it looked as if had always been that way”. An authentic frame from that period is the ideal image that Karl Pfefferle has in mind. However, because 98 percent of all pictures are, over time, removed from their original frames, he has a lot to do in his Munich workshop. Since the Gothic period, every owner has demonstrated his pride in his collection by revamping his pictures with new frames. August the Strong in Dresden endowed all his old pictures with Rococo frames. “Which today is considered to be historical and no longer called into question”, elucidates Pfefferle. “It was only at the beginning of our century that people started to think that maybe Cranach knew how to frame something”, Pfefferle added. “One goes back to the language of shapes and forms that were in common use at the time of the picture.” With the decision to replicate historical frames, the business really took off. Grandfather Pfefferle bought everything that he could get at a favourable price back then. Today, frames are collectors’ items and as such are now expensive. Karl Pfefferle owns around 2000 original frames from Gothic onwards, which his ancestors gathered together. He himself even searched for rare specimens with his father at art dealerships in Italy. He will not part from one single piece – they all serve as models for his replicas. On one wall, puffed-up, Italian Baroque frames flaunt themselves. A 2x1.50 metre replica costs DM 10,000. The original would be well over that – however: “Because of expensive labour costs, the original could occasionally be even cheaper than the copy”, Pfefferle admits. However, original frames are still scarce articles. On another wall that is dedicated to the period around 1800, a small Louis XVI oval frame from 1780 is hanging. Although tiny, it costs DM 2200 as it is decorated with carvings and an ornate bow. Yet another wall is adorned with Rococo frames, and a further one still by Renaissance frames. In between, a huge picture by the Berlin artist Rainer Fetting is leaning; the frame made from simple, stained pear wood costs only DM 800. With the advent of the post-war art period, frames thinned down to narrow borders. “For me the frame has an absolutely subordinate function”, stresses Karl Pfefferle. It has to enhance the distinctiveness of the picture. “If it is a delicate Impressionist picture, the frame has to rescue it from fading away. For an Impressionist painting, it has to be something very delicate, the tone of which responds to the picture but does not in the least repeat the colours of the picture – one must not be tempted to paint alongside.” He also considers it a mistake to try to use the frame for interior decorating purposes. The frame must always remain one step behind the picture. |

Incidentally, the majority of French Impressionists stuck their delicate paintings into heavy, bourgeois, gold frames with chamfers. Many artists even took old frames and painted them. Karl Pfefferle would never dare to do that. “Only an artist is completely free. A frame manufacturer must not desire to play the artist.” At the moment, he has to frame an early van Gogh. No easy task. “We decided on something dark and austere, which brings out the colours.” As Emil Nolde prefers a certain kind of frame, the Pfefferle workshop handcrafts frames for him from simple, black oak slats. “They keep the flaming pictures grounded.” He likes to give a Picasso a solid, old-German Baroque frame because Picasso himself liked and collected old frames. Franz von Stuck, who decked his paintings out in pompous, painted and gilded frames, also created a standard frame “which was markedly innovative for his time”, Pfefferle believes. The frame served Stuck as experimental ground, stage and fragment of wall, as “homeland of the picture”, and last but not least as a trademark. Only with a frame did a painting have the aura of being an “authentic piece” and so became a complete piece of artwork. During the re-framing of von Stuck’s “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” at the Villa Stuck in Munich in 1918 to which Karl Pfefferle was called in, he decided on an authentic multi-area frame. His decision was, in addition, based on his observation “that, in many cases, Stuck worked against the picture format when framing, i.e. adding a transverse arrangement at the top, and with a broader section of frame at the bottom”. When Karl Pfefferle re-framed Sandro Botticelli’s “Madonna and Child” in Henning Strube’s restoration atelier, he was inspired by the tabernacle frame of Leonardo da Vinci’s picture “Madonna and Child”. “In all cases in which there are no available authoritative drawings or photographs of the original picture frame, I tend to choose as simple a type of frame as possible.” Once a Japanese man came into his workshop with a print of a Botticelli painting. He had Karl Pfefferle make him a replica of an Italian tabernacle frame from 1550 for the poster that he had bought in a department store. The cost: 25,000 DM. Alexandra Lautenbacher Rescued from fading away Die Welt, 7th March 1998 |

|

|

|

||

Der Kunsthandel, Issue 1/1996, Pages 39-40 The signs of age counts here Frame manufacture, gilding workshop and gallery, Karl Pfefferle in Munich Our contemporary throwaway culture has altered not only our attitude to most things but also the nature of the things themselves. There are hardly any industrially produced products that tolerate growing old gracefully. In complete opposition to this trend towards new and shiny things stands the Karl Pfefferle Workshops’ programme. Karl Pfefferle and his present team of 16 co-workers are occupied exclusively in the production of gilded and unique frames, and in replicating true-to-style historical frames. Each piece, made from A to Z by hand, is created in line with age-old handicraft techniques. Right at the start of the Industrial Revolution in Germany, the tendency associated therewith towards lack of historical awareness in day-to-day life produced a cultural counter-movement. The yearning for consistent values and a nostalgic enthusiasm for history and antiques led to the emergence of Historicism in the art field around the middle of the previous century. Munich was a stronghold of the prevailing trend at that time. That tempted Karl Pfefferle’s great-grandfather, a trained Fassmaler (=painter and gilder) from Tyrol, to come to the Bavarian capital in 1858. The founder of the Munich Pfefferle dynasty participated as church painter and restorer in diverse new buildings in the Neo-Gothic and Neo-Renaissance styles. Of course, he and later on his son produced and restored pictures frames completely on the side. It was only when the “Gründerzeit” (= the period of rapid industrial expansion in Germany after 1871) building boom was waning while at the same time the demand for beautifully framed decorations for citizens’ parlours was constantly increasing, that at the turn of the century a local art dealer gave the impetus for the present-day direction of the Pfefferle company. The handling of painted and gilded carvings in connection with architecture, of wall paintings and stucco decorations did not end there though. So it came about that the father of the current owner of the company worked on the reconstruction of the Cuvilliés Theatre in Munich during the 1950s. After the early deaths of his father and his uncle, Karl Pfefferle took over the running of the family business in 1967. He was just 20 years old and did not just have his “Abitur” (= German Advanced School Leaving Certificate) in his pocket, but had also successfully passed the guild examination in the handcraft of gilding. From the very beginning his particular preference was for the company-owned collection of historical original frames and replicas. He has accumulated around 2000 models up to now in his storerooms. Baroque and Rococo styles, Empire and Classicism frames, and Biedermeier mouldings, broad with black corners, are piled up on and next to each other. Another of Pfefferle’s concerns is the merger of Traditional and Modern. In 1983, therefore, he founded a gallery in Rumford Street. There he displayed outstanding works of the New Figurative Art. One of his most spectacular exhibitions was dedicated to the work of Rainer Fetting. His by then excellent reputation as a gallery owner also took Karl Pfefferle even further in the frame business. Now as then collectors of antique artworks trust him with the framing of their treasures. In addition to this, there are, increasingly, the frame commissions pertaining to the refinement of art from the past three decades. |

At the business premises in Gewürzmühl Street, Munich, paintings by Gerhard Richter, Elvira Bach, Francesco Clemente or A.R. Penck await the ultimate dressing-up. They will indeed have to wait for this as a good, unique frame takes time. Everything is taken very seriously in the House of Pfefferle and executed extremely meticulously. Even a simple, stained moulding around a small decorative graphic illustration or a silhouette is solidly handcrafted from start to finish, with mortised corners and hidden mitres. At the very most, only 800-1000 commissions per year – depending on the size and construction – can be carried out. Bernd Zachow |

|

|

|

||

Süddeutsche Zeitung 1959 Art does not matter to the woodworm Swiss contract for the Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments The Leinberg Madonna in new glory “This altar, which originated in Tyrol, was acquired from a private owner in Munich in 1952. In 1953 it was restored there and in the same year transferred to the Church of Saint Peter in Wil.” Behind this short text on the banner being swung by a little angel in the top left corner of the Gothic shrine hides a story that tells of the importance of the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments. The altar, on which Munich artisans (the Karl Pfefferle Company and the sculptor Hans Vogl) worked for over a quarter of a year, will be taken within the next few days to Wil, a little old town in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen. “Only due to a coincidence did the citizens of Wil hear that there was a beautiful Gothic shrine for sale in Munich”, reports the director of the State Office, Dr. Ritz. The citizens of Wil enquired if it would not be possible for the Munich Office to take on the restoration work on the altar, which required in parts a totally new reconstruction. Dr. Ritz agreed. Together with Professor Schmuderer, the one-time department head and current special evaluator at the State Office, he worked out an evaluation of the altar complete with the total conversion of the church in Wil. The Swiss were so impressed by this that they then wanted advice from the Munich specialists about the restoration of their cathedral in St. Gallen. There are currently around 30 scientists, artists, architects, craftsmen and technicians working in the Office for the Preservation of Monuments, which is next to the National Museum. There is a department for the preservation of historical monuments, one for pre-and-early history, and one for the inventory, the records of all the assets of all the Bavarian art-historic monuments. Besides that, a Museum of Local History department takes care of the non-state museums. The practical work is carried out in their own workshops. Here the old mountings of precious artworks are laid bare, and sculptures full of woodworm holes are saved from decay by being treated with special agents. Several paintings, a crucifix, four pieces of relief work that were once hanging in the old Heart of Jesus Church in Neuhausen, and the most precious piece at the moment, the Leinberg Madonna from St. Martin’s Church in Landshut, will be helped by the restorers to new glory. |

Very often other periods, especially the 19th century, daubed over the beautiful original items. The restorer, using a small knife, first of all carefully scrapes away a tiny piece. He exposes a little “window”. Sometimes, in this way, five or six different layers of paint are discovered. The original colours of the Leinberg Madonna appeared again almost untouched. Some of the figures are so riddled with woodworm that they look almost like sponges and are only held together by the paintwork. In spite of this, they can be salvaged, “but only with the greatest of care”, says Dr. Ritz. “Too much restoration can de-value an art object.” No one denies the duty to take care of historical monuments. “But with respect. One should not restore too much. A cook’s standards of cleanliness are misplaced when associated with historical monuments. Why should one not be able to see from a picture that it is 500 years old?” Dr. Ritz and his people are supervising, among other things, also the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Church, St. Michael’s Church, and the Old Academy, as well as the work on the cathedral. He mentions the installation of a glass painting in the Church of Our Lady as being a particularly difficult task. On a personal level, the front garden of the State Library is very dear to his heart; in his opinion it should not be torn down or converted. Edith Eiswaldt Art does not matter to the woodworm Süddeutsche Zeitung 1959 |

|

|

|

||

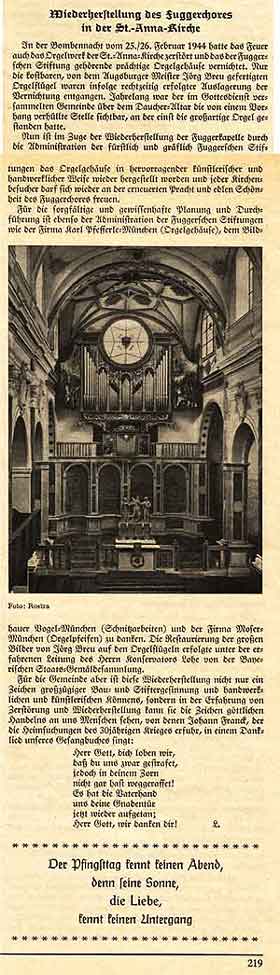

Origin unknown, around 1949, Page 219 The restoration of the Fugger Choir in the |

|

|